11 Nov The New York Times Interviews RZA About Shaw Brothers Films

Read the original at the New York Times.

RZA watched the Shaw Brothers’ martial arts classic “The 36th Chamber of Shaolin” for the first time on television when he was 12 years old. Two years later, he saw the 1978 movie on the big screen “in a seedy Times Square theater on 42nd Street,” he recalled. He went with his cousin Russell Tyrone Jones, who would grow up to become the rapper Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

Kung fu movies were much more than a hobby for these Staten Island musicians and rappers who helped form the Wu-Tang Clan in the early 1990s and named its debut album in homage to the film: “Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).” RZA went on to do significant film work on his own as an actor, soundtrack artist and director. (In 2012, he acted in and directed “The Man With the Iron Fists” and wrote its screenplay with Eli Roth.)

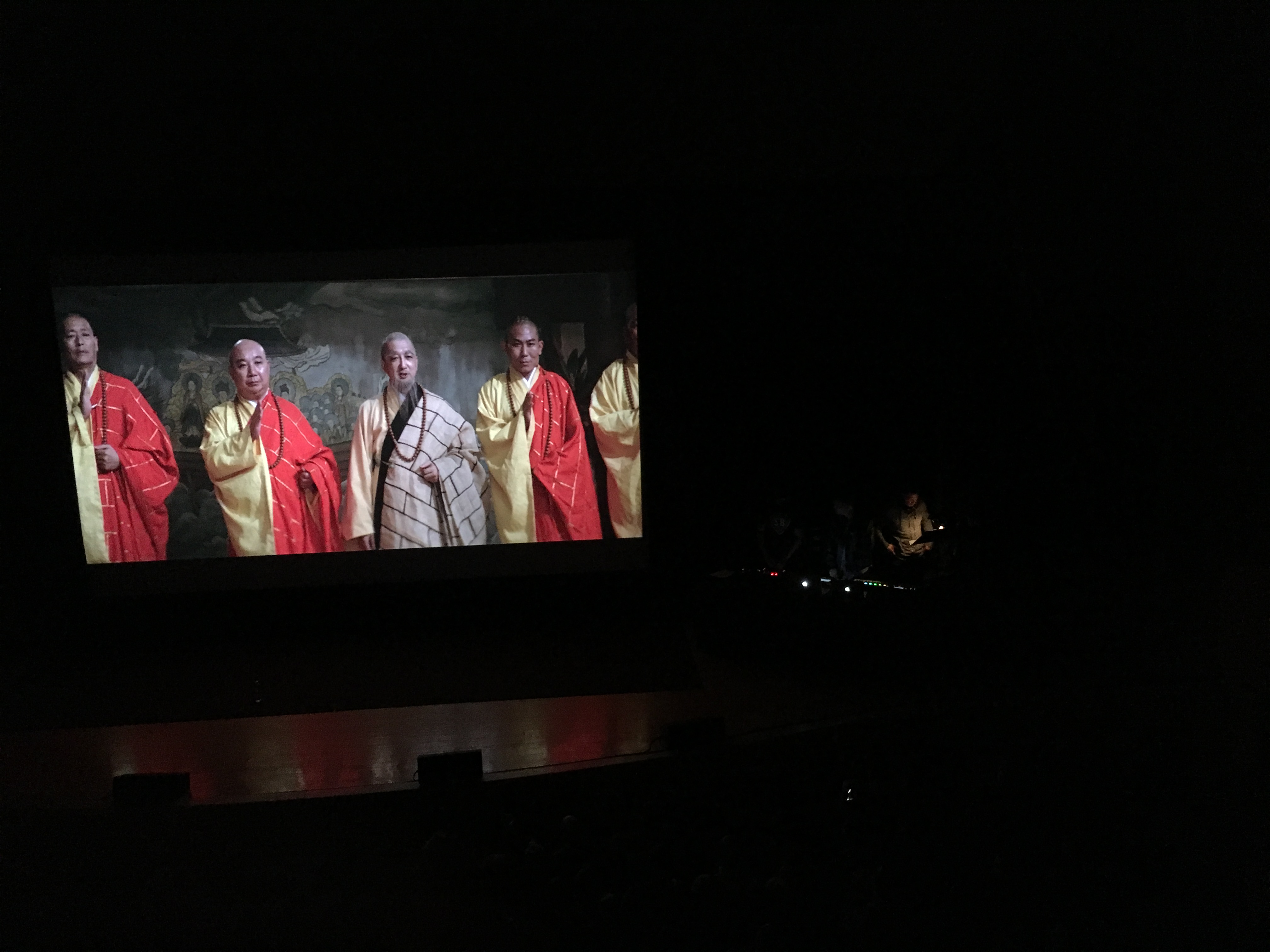

Today, RZA estimates that he has seen “The 36th Chamber of Shaolin” more than 300 times, making him uniquely qualified to perform original music as the film screens at Town Hall on Thursday night. His “live score,” which he has performed before for public audiences in Los Angeles and Austin, Tex., consists of more than 50 instrumental tracks, beats and vocals. Earlier this week, he spoke about kung fu heroes and the future of hip-hop. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

How do ancient Asian mythology, kung fu movies and hip-hop relate for you?

Growing up, all of my friends would set their schedules to the showing of kung fu movies on TV. At 3 p.m. on Saturdays, everyone would be inside watching kung fu movies, and by 5 p.m. we were back outside doing the things we saw in them, from the dancing to the style of talking, mimicking the patterns of movement, and of course being inspired by the music.

The influence of the Shaw Brothers films on my work has been profound. In addition to the richness of Asian culture, we at Wu-Tang were fascinated with the struggles between the oppressed Chinese villagers and the repressive Manchu authority and how it mirrored our own experiences growing up as black kids in America’s inner cities. We didn’t know that that kind of story had existed anywhere else. The universal message that strong determination could actually lead to success despite one’s circumstances would be one that we would adopt.

What was it about this specific film that spoke to you, and how does it continue to inspire you?

There are numerous parallels between my life and the film. This particular film not only speaks to oppressed people, it features one man and how he can successfully deal with obstacles, teaching you tenacity and determination in the midst of all problems.

This film also helped us, as young men of Wu-Tang, better understand the universality of struggle. We started to understand that icons like MLK, Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey and many others were messengers to heal conflict and strife, as well as people like the Kennedy brothers, John Fitzgerald and Robert Francis — whom my mom named me after.

As hip-hop ages and you are becoming one of its elder statesmen, how do you feel the genre is handling growing older?

I see hip-hop continuing to be a guiding light for the evolution of society. As one of the newest forms of music, hip-hop has always brought communities and cultures together, and now that our elders are entering their 50s and 60s, we can again look to kung fu culture for an example on how to mentor the next generations. We can look at the different phases of different music genres as they matured: Funk had Roy Ayers, the blues had B. B. King, soul had James Brown, rock had the Rolling Stones, and pop had Paul McCartney.

And we all have Quincy Jones. It’s a beautiful thing that hip-hop now has our godfathers and elder icons — for example DJ Premier is a strong advocate for younger artists, DJ Scratch always makes himself available. This is a core element of kung fu culture. The youth have to go to the elders for mentorship, and that’s what’s happening in hip-hop.

A few of the younger artists that stand out are those that are particularly consistent in promoting a message with their music, like we tried to do at Wu-Tang. J. Cole, Kendrick Lamar, Drake — these are all artists that are starting to reflect as young men, and not waiting until they are aged to really wrestle with issues in the world. I also love the playful music of acts like Rae Sremmurd and G-Eazy, they bring the swag, braggadocio, the ego, and the humor, but still within the cultural truth of hip-hop.